THEY BURIED BOY TOGONON LAST SATURDAY morning. The heavens, which have been crying since he died, stopped crying to let the sun through, long enough to permit his burial under sunny skies, then burst again into copious tears in the afternoon.

At the necrological rites the night before at the National Press Club, at least one speaker shed his own tears during his spiel. But even in death, Boy Togonon was still doing his good deeds. Veteran journalists, who had stayed away from the NPC because of disappointment with the abuses and irresponsibility of NPC officers, trooped back to the NPC Plaridel Hall for the necrological rites for Boy. Some of his fellow artists went home from foreign shores for his burial. And many of the old Express staffers I have not seen for years showed up at the NPC. But isn’t it ironic that journalists get together at the NPC only when one of their colleagues die? But for one night at least, journalists mourned together and reminisced the good times and the happy moments with Boy Togonon. Boy had been my close friend for almost three-fourths of my life.

I first met Boy Togonon when the Daily Express was being organized back in 1971. I was then the managing editor of The Evening News but Pocholo Romualdez invited me to be the managing editor of the new newspaper. I accepted because I would be working with the best journalists then: Joe Bautista, my journalism professor, Manolo Villareal, Johnny Perez, D.H. Soriano and Pocholo. Not only that, the art department was organized by Malang the painter-cartoonist, and the artists he recruited were young graduates from the University of Sto. Tomas: Boy Togonon, Benjo Laygo, Dante Munsayac and Arnold Adao. Their chief was Danny Franco, a talented painter but now better known as the fashion designer. Their guru was the veteran painter, cartoonist and art director Hugo Yonzon Jr. Cartoonist Larry Alcala came often to visit. I had assigned him to do his “Slice of Life” cartoon series in the Weekend Magazine of the Express. For photographers, we had a talented bunch, too: Jun de Leon (now better known as the celebrity fashion photographer), Ed Santiago, Manny Goloyugo, Noli Yamsuan and others.

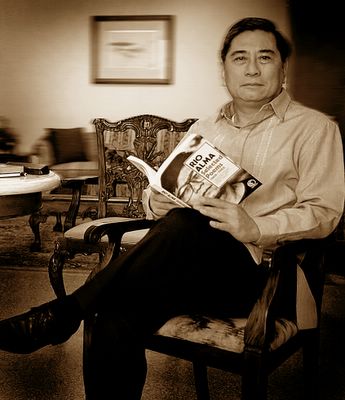

I mentioned the artists and photographers to give you an idea of where and how Boy Togonon honed his artistic and humorous skills. By the way, Boy’s real name is Romeo but he didn’t want to be called by that name. It sounds too romantic, he would say, and makes women suspicious. He preferred Boy Togonon or Boy Togs or just Togs. Close friends usually used the second nickname.

The art department of the Express was a cheerful place. Whenever I wasn’t busy at the news desk, I went to the art department and we shared stories and cracked jokes with the artists and photographers. We all watched while Hugo Yonzon painted his pieces. Many of his best paintings were finished while swapping jokes and banter in that room. Amid all that hullabaloo, Boy Togs stayed at his drawing table doodling for ideas, or finishing his editorial cartoon or comic strip “Melody” for the day. The character of Melody, by the way, was a domestic helper Boy Togs created with the late Teddy Berbano, and antedated the era of the DH as OFW.

Since then, Boy Togs had been with me for the most part. Shortly before the Express closed down due to a strike after the 1986 People Power revolt, I organized the Tribune. Boy Togs resigned to go with me. When the Daily Globe was set up, Boy Togs and I helped organize it. And when I moved to The Manila Chronicle, Boy Togs was with me as art director and production manager.

It was only when I joined the Inquirer that Boy and I parted ways, he joining a few other newspapers. But we were never far apart. I saw him court his future wife, Sonia. I was a godfather at their wedding. I saw his children grow up into the good-looking young men they are now. We did projects together; we often had lunch or dinner together, or just horsed around with other mutual friends. We witnessed him build his house in Bacoor, Cavite, and visited often when it was completed. We had lunch regularly at Plaridel’s watering hole every Monday.

The Monday before he died, we had lunch with Plaridel friends. When I arrived, he was sitting on a bench at the lobby. I asked him what he was doing there; the lunch was on the second floor. I can’t go up to the second floor, he answered.

You can, I said. Come on, we’ll go up together. So we went up the stairs slowly. He rested at the first landing. After a while, we again slowly walked to the top of the stairs. I went inside but Boy Togs sat on a chair beside a table to rest. He was joined there by Jun Bautista who, like him, has breathing problems.

We had a very happy time together then, swapping jokes and stories, and we stayed till mid-afternoon. I didn’t realize it was the last time we would be together. Maybe, that was the reason that last lunch together was so happy.

When the news was phoned to me that he had died, it was like I lost a brother. Boy Togonon was a brother, a friend, a colleague, a companion, a confidant, a sharer of secrets, a loyal and trusted pal.

With Boy Togonon’s death, I not only lost a brother and friend, the Philippine media lost a talented journalist.

He was an affectionate husband and a doting parent. He drove his wife to office every morning. When his wife went out of town, he accompanied her—not only to the airport but to her destination. He always had stories to tell about his children. He was already talking about the prospect of having grandchildren when he died.

We will all miss Boy Togonon.